Note: Since this story was published, the Rutters have relocated to Townville, SC

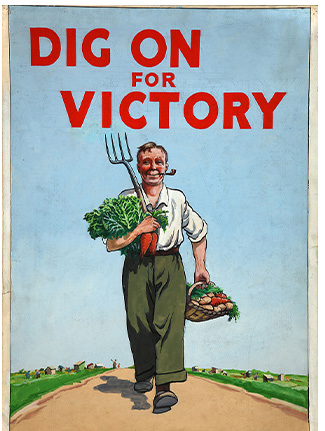

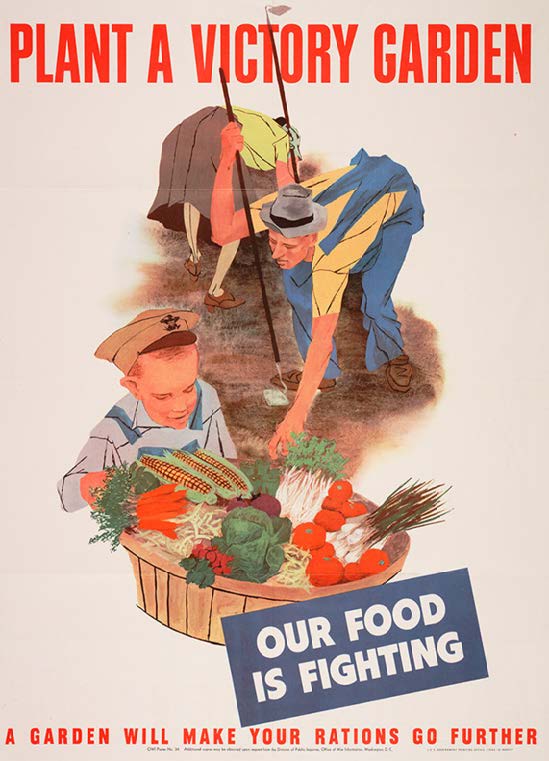

A classic World War II poster brings to mind Norman Rockwell’s America. A man and woman tend a garden. A boy in coveralls holds a wooden basket overflowing with corn, tomatoes, onions and lettuce. The headline? PLANT A VICTORY GARDEN. White words on blue proclaim OUR FOOD IS FIGHTING. Red words on white state, A GARDEN WILL MAKE YOUR RATIONS GO FURTHER.

The messages in all caps shouted for a good reason. Rationing constituted an essential war strategy; the boys abroad needed food. The government rationed sugar, butter, milk, cheese, eggs, coffee, meat and canned vegetables. Getting fresh vegetables challenged people.

The solution: Victory Gardens. Nearly 20 million Americans answered the call. Colorful gardens sprouted in backyards, empty lots and city rooftops. Fruit and vegetables harvested in home and community plots were estimated at nine to ten million tons, an amount matching commercial production.

A Farewell to Arms

The lessons of World War II victory gardens were not lost on Kara and Matt Rutter. They established Project Victory Gardens as a veteran-operated, non-profit in March 2019 and began an agritherapy program. Today it supports veterans and a sustainable food system backed by deep experience.

As veterans, the Rutters wanted to find a way to continue serving the nation and their military community.

“We wanted to find a way to utilize agritherapy to help veterans, service members and their families,” said Kara. “But it had to be more than that. In the Army, we were trained to be problem-solvers. We saw three problems: food insecurity, the challenges of two decades of sustained war and an aging farmer population. So, what is the solution? The same solution that worked during World Wars I and II: Victory Gardens.”

The Rutters decided to use their Aiken farm to train and encourage both their military family and the community-at-large to plant gardens. They wanted people to benefit from agritherapy and animal therapy and gain the knowhow needed to launch their own agribusiness, thereby increasing food security. Kara joined the Army in 1997 as a cook. She served as a member of the U.S. Army Culinary Arts Team.

“I competed in the International Culinary Olympics in Germany,” she told me. “In early 2003, I deployed to Iraq and prepared 125,000 meals from a mobile kitchen trailer in the desert. When I returned from Iraq, I transferred to the Pentagon, where I spent three years cooking for Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.”

Matt joined the Army in 1998 as an infantry soldier. He spent more than half of his career overseas with multiple deployments to Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

“I served in Germany and deployed to Kosovo during my time in the Infantry. I attended the U.S. Army Sergeant Major Academy and spent another year in Germany, before transferring to Fort Gordon, Georgia. My final assignment was as the Command Sergeant Major of the Processing, Exploitation and Dissemination Battalion at Fort Gordon, where I led 600 soldiers and 400 civilians.”

Kara and Matt met in 2015 at the Sergeant Major Academy in Fort Bliss, Texas.They served a cumulative 45 years in the U.S. Army, culminating at command sergeant major and sergeant major, respectively. Both are qualified Master Resiliency Training instructors. When they retired they put their training, skills and experiences to work in Project Victory Garden. From day one the reaction and support were tremendous.

Welcome to the Farm

Project Victory Gardens sits on twenty beautiful acres with a three-acre pond. There’s no typical day on the farm.

“We keep the animals on our schedule,” said Matt. “We spent a lot of years waking up early and we try not to do that anymore. We do morning chores at 8 a.m. and evening chores an hour before sundown. Between those times, most every day is different. Lately, it has been birthing season, so we have been running fence for pastures. We need to get the animals moved into the new pasture the day before they deliver.

“Our biggest challenge is building as we go,” he noted. “As we scale the farm, we’re just barely staying in front of what we need for our animals: new pastures, goat birthing areas, pig farrowing huts. Starting a new farm requires you to prioritize what is absolutely necessary to keep the farm moving forward and keep your animals safe and productive.”

Kara describes the work as a complex operation. “We want veterans to be able to come here and find their niche. So, we have three types of pigs, three types of goats, turkeys, laying chickens and broilers, ducks, quail and bees, in addition to the various planting methods and orchard. We have so many irons in the fire that sometimes it is difficult to make those prioritizations.”

Among those irons? Advocacy.

“We spend a lot of time advocating for South Carolina farmers and specifically veteran farmers at the state and national level,” said Kara.

“We’re proud to take up the charge to advocate for issues like new meat-processing facilities and rural broadband for our members.”

South Carolina Leads the Nation

The Rutters are in fertile ground as veteran farmers and South Carolina go. Nationwide, 9.7 percent of agricultural producers are veterans. At 14 percent, South Carolina leads the nation in agricultural producers with military service. From raising corn to cows, lavender, mushrooms and more, South Carolina’s veteran farmers generate more than $416 million on 869,220 acres. On a broader scope, the state’s veteran farmers work in aquaculture, grain, other crops, greenhouse, vegetables, beef, sheep and goats, and poultry.

It makes sense that South Carolina leads the nation in veterans who farm.

“The military recruits heavily from the rural Southeast,” said Kara. “Many of our bases are located in or around the state, so it is natural to return to or stay in South Carolina. In fact, one in ten adult South Carolinians are veterans. Matt is a twelfth-generation South Carolinian; his roots run deep in the Palmetto State, and he is very proud to be farming land near where his ancestors settled.

“I am originally from Montana, but I find South Carolina to be a wonderful place to retire. Agriculture is the number one industry in the state, so we expect to find many veterans within those ranks. Our hope going forward is that we see a decrease in the average age of the veterans farming in South Carolina. That is ultimately our goal.”

Matt believes the project resonates with veterans because it gives them a sense of purpose.

“There are things (animals and plants) that rely on us every day for food, water and care. So every morning when we wake up and walk out to do chores, they are there. They might not stand in formation, but they’re waiting on us.”

Kara said that getting back to the land resonates with many of their peers in the Army. “Eventually Project Victory Gardens will pop-up across the United States,” she predicted.

Kara believes vets feel as she and Matt felt upon retirement. “When we talked about what we wanted to do when we retired, we first started with a list of what we didn’t want to do. We didn’t want to retire and show up the next day in civilian clothes working in the same windowless rooms we retired from. We wanted to be outside and work on the land. Petting baby goats, farrowing piglets and planting in the soil are so fulfilling and centering. Many of us spent years bouncing around the world with no place to call home. To be able to till a piece of land or have an animal that relies on us every day for its basic needs is incredibly rewarding.”

The From Troops To Tractors

Making the transition from troops to tractors offers a promising path to many of the 250,000 service members who transition out of the military each year. Project Victory Gardens’ agritherapy, animal therapy and agriculture education program cultivates healing and resiliency in veterans. Through exposure to farming techniques, artisan homesteading classes and resiliency exercises, Victory Gardeners can experience a reawakening of the sense of purpose they had in the military.

The Rutters are active members of the military and veteran community in addition to the Aiken community. Matt is the founding president and Kara is the communications director of the Farmer Veteran Coalition of South Carolina. Kara established the Third Army Association in Sumter, and Matt served as treasurer of the Military Intelligence Corps Association, Master’s Chapter. Matt is pursuing a Master’s degree in agricultural education.

After a combined 20 moves and decades spent overseas and in combat zones, they never take for granted a morning when they wake up on their farm. They recognize the good things farming does for veterans.

“We are so proud to represent military veterans in the South Carolina agriculture community,” said Kara. “Farming gives us a second opportunity to serve our nation, this time by feeding it. I have spent a lifetime in food service and I am honored to be a source for farm-raised food for our community.”

“If you are a veteran, trying to find your place in the world,” said Matt, “your calling might be farming, because it gives you a piece of your military service in taking care of animals and a piece of your military service by feeding the nation.”

Project Victory Garden—it’s more than food. It’s a way to solve crucial problems. Learn more about it at www.projectvictorygardens.org and see how its programs cultivate resilience in veterans.